OUR

RHYTHMS, OUR COLLECTIVE IMAGINATION

THE

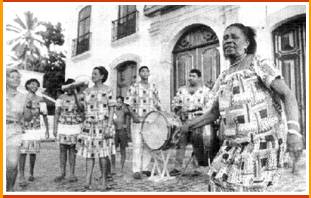

BACNARÉ GROUP. Photo: Hans von Manteuffel |

|

The influence of the Brazilian

natives, the Africans and the Europeans, has provoked an

extremely unique

cultural identity in the Northeast. An identity that is revealed in its multiplicity

of rhythms and artistic manifestations. It shows the face of our

people who, in their everlasting fight for a dignified life, are

eternally open to the day-to-day blossoming of happiness. |

When

you watch people of all ages accompanying and singing together with Dona Selma's

Coco, it is quite apparent how enjoyment, dance and

music (with its

playful, contagious verses), are so important for the people of the

Northeast. Today, this great conquest is clearly represented by the coco -

the coconut dance - an ancient rhythm that has been retrieved and firmly

planted in the Northeast.

Within

the beauty of its dance and the strength of its verses, many folkloric

experts have created definitions regarding coco. The majority agree

that it was originally a work song of the coconut pickers, and that only

sometime after, it was transformed into a dance rhythm. Some affirm that it

first made its humble appearance in the rural areas, on the sugar plantations, and later

spread to the coastal

regions, after which, it made its way to the more refined environments. Others, on the other hand, believe that it

is essentially a dance of the beach, because of the predominance of

coconut palms found in this region. In relation to which state of the

Northeast the dance actually appeared first, the disagreements are even greater and more diverse.

References to the three states of Alagoas,

Paraíba and Pernambuco are found in the existing texts, indicating them

all to be

the probable "owners" of this dance. So, where is its

real origin? This is a vacuum to be filled by those who are

curious, interested and have the spirit to discover. In the middle of so

many doubts,

one thing is certain: the coco has its origins in the people - the

masses. With regard to its

form of expression, the researchers define many 'types of coco'. It would

not be a trustworthy notion to be content with just one classification, before such

an adversity

of definitions. What we have noticed is that the variations of coco

begin with

the differing names given from one region to another. These variations can be

identified in aspects of the dance itself, and mainly in the metric differences of the

sung verses. Overall however, the coco is presented in one basic form: the

participants form lines or circles in which they carry out a characteristic

type of 'tap dance', react to the chorus, and clap their hands to the rhythm. It is

also very common to find a leading singer, and it is from the moment that

this person begins to sing, either improvising or or with traditionally

known songs, that the festivities begin.

"Coqueiro, tá de coco novo

minha gente o que é que há..."

("Hey! Everybody! The

coconut tree is full of coconuts - is there anything wrong with

that........?)

The coco can be danced with or

without shoes. Also, it does not have its own appropriate costume. In order to participate,

the people can use any kind of clothing. There is also, apparently, no special time of the year

to dance, although it is

more often seen in June. Musically speaking, there is a predominance of

percussion instruments. According to folklore researchers, the most

commonly used instruments are - ganzás (a kind of maraca), bombos

(drums), zabumbas (a deeper drum), caracaxás (a kind of scraped rattle,

often made of undulated metal and scraped with a small stick to produce

the sound) and cuícas (a drum -like instrument that

makes a squeaking sound).

However, to form a circle of coco it is not necessary to have all, or

indeed any of these

instruments. Very often, the dance takes place with just the clapping of

the participants' hands.

Within its general characteristics it is possible to notice one

distinct distinguishing feature - community spirit. There is always a very happy atmosphere where men, women, children

of all social classes sing and dance together without distinction. In what

is referred to as its ethnic influences, the African influence is most prevalent,

mainly in its rhythm, and most certainly in its movements. But, there is also a

very strong native contribution to the choreography. Both the circle and

the lines are aspects that were inherited from our natives.

DONA

SELMA'S

COCO. Photo: Eduardo Queiroga |

|

Today the

coco is ever present in the festivities of our people. Selma and

many other traditional conquests are examples of the resistance and

strength of an authentic and original manifestation. This contagious

rhythm has influenced numerous popular composers through the ages, and even

contemporary Pernambuco music . The famous Jackson do Pandeiro influenced Chico

Science, Alceu Valença and many other local musicians who have

consistently searched for this playful aspect in the creation of

their work. |

|