THE

PASTORAL -

BETWEEN

THE SACRED AND THE PROFANE

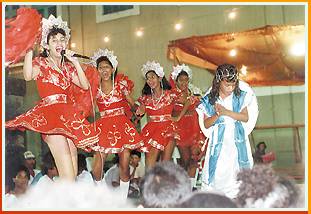

THE

VICTORIA REGIS PASTORAL . Newspaper

photo archives |

|

Throughout the research

dedicated to the dramatic manifestations that in some way express the

Brazilian people, principally the

dramatic dances, it is a proven fact that all the origins are of a

religious nature, and not profane. Gilberto Freyre and Mario de Andrade, for example, are unanimous in affirming that, even when

their basis or links are attributed to economic factors, these

popular artistic manifestations, together with any of their

variants, originate from religious mysticism. |

One

further important characteristic highlighted by Mario de Andrade in "Dramatic

Brazilian Dances" is that - "within the majority of our

dramatic representations, we either encounter death and resurrection as

the main theme or, as in the case of the Pastorals (and the Cheganças - a

typical Northeastern dance manifestation),

the fight between good and bad, thus characterizing the notion of danger

and salvation".

In the pastorals that originate

from the Iberian Peninsular, the concept of death and resurrection does not

appear in a definitive manner. However, in the so-called Profane Pastoral

we encounter the 'fight' between the blue group and the incarnate (red)

group.

This reveals the idea of confrontation, in which the incarnate group is

considered to be the more audacious and daring of the two groups.

Nonetheless, as Mario de Andrade reveals, it was the religious objectives

that gave them, "their [the dramatic dances] first origins,

their reason to be psychological and to become traditional".

It is also important to point out that the religious

character of these manifestations is also full of theatricality. A

theatricality that is born out of the celebration rites to the Greek god Dionysus.

However, to quote Mario de Andrade once more - " it is these profane,

social elements that little by little, have become more important, and

have gradually destroyed the primitive religious objectives of theatre.

And, indeed, it is these profane elements that have gradually come to dominate".

This phenomenon took place in Greek drama, the Japanese Noh theatre, and

the Medieval Mystery plays, as well as in our own Brazilian dramatic

dances.

It is also worth noting that

all our popular dances contain a dramatic section (even if it is an

improvised text), music and their own particular manner of dance. All these elements

reveal the three basic ethnic origins of the Brazilian people - Native,

Portuguese and African.

THE ORIGIN

The origin of the Pastoral also has

connections with Iberian popular religious drama. In fact, in Spain as

well as in Portugal, important Catholic dates were not only

transformed into ecclesiastic festivals but also popular

festivities.

From as far back as the end of the 16th. century, several authors have

recorded presentations of plays connected to Christmas, the Three Kings,

Easter etc., with a mixture of pastoral and allegoric elements, dances,

texts and songs. This type of theatre established itself in Portugal with

the Galician-Portuguese ballads, which were the original source of our

pastorals. These ballads were sung by a soloist, with a chorus sung by a

choir dressed as shepherds who represented the Nativity.

Even at the very beginning, the Pastoral,

was never really popular with the bourgeoisie, but it gained ground

because of the enacted Nativity scenes. Systematically, the Pastorals were

danced in front of the 'lapinha' - the word given to special grottos where

the Nativity scene was reenacted in a totally static form.

The researchers seem to agree that Christmas and Nativity festivities began to

appear at the beginning of the 10th. century.

According to the research of Mario de Andrade, " the idea of

commemorating the birth of Christ through dramatic representations first

began thanks to a certain monk called Tuotilo, who died in April of 915 at Saint

Galo's Abbey, in the central region of Germany. It was here that the

so-called Sequences and 'Tropas'

first appeared. The 'Tropas' - a kind of Nativity musical play -

consisted of new texts and melodic phrases, interlinked with official

religious texts of the church and sung in Gregorian chant.

THE SHINING STAR

PASTORAL. Newspaper photo archives |

|

Very soon

after, they began to be presented in France and England, where they

gradually transformed into medieval liturgical dramas. They were

divided into three main sections : The heralding of Christ's

arrival, the adoration of the Kings and the slaughtering of the

innocent. The first two themes remained intact and quickly spread

throughout western Europe and Portugal, thanks to the Jesuits, who

finally brought them to the Brazilian colony. |

THE

NATIVITY SCENE

Nativity scenes only appeared in the 18th.

century with the Umbrian religious movement, and traditionally, pastorals

were danced in the immediate foreground of these scenes. The invention of the Nativity scene is

attributed to Saint Francis of Assis. Around 1510, the theme was taken up

and appeared in small dramatic plays such as those by Sybilla Cassandra

and Gil Vicente, as cited by Pereira da Costa. In Portugal, presentations

of the nativity plays were not recorded until the end of the 18th. century.

Citing Pedro Fernandes Tomás, Mario de Andrade observes that, " the

'Pastoral Autos' (see explanation of 'Auto' below) or The Pastoral Nativity

plays, as they were commonly known, were theatrical compositions that were

performed in numerous localities around the country during the Christmas

festivities, New Year and Twelfth Night. They comprised a series of

small 'autos' (dramatic pieces) and were presented in private

houses

on improvised stages with very simple scenery. Very often, the scenery was

made of pine or bay tree branches spread over the walls of the stage. At

the back of the stage, the traditional grotto could be seen with the Virgin

Mary attending to the baby Jesus, with Joseph by their side. The manger

could also be seen together with the symbolic animals - the cow, the mule,

and the ass on which Mary had made her journey from Nazareth to Bethlehem.

A curtain covered the grotto, and as the ingenuous scenes of the 'autos'

would finish, so the curtain opened and the cast would fall to their

knees in reverence to the baby Jesus. The most popular farces performed between the

'autos' were - The Blind Man, the Young

Maiden, The Friar and The Pious Woman, The Sweet-Toothed Woman etc. There

was also a type of prologue in which would appear Night, the Moon, the Sun

and Attention and other symbolic entities. In ' The Three Kings Auto', Herod,

the King of Judea, would also appear ordering the slaughter of the

innocent, while remaining indifferent to the pleas of Raquel. It is thought that

these presentations date from the 18th.century and have survived in

manuscript form"

In Brazil, and more specifically in

Pernambuco, according to Pereira da Costa, the first appearance of the Nativity

scene probably took place at the end of the 16th. century, in the Franciscan

Convent of Olinda. The person responsible for this was friar Gaspar de

Santo Antônio - the first man to receive religious orders in the new

colony. Thanks to documented evidence by the Jesuit priest, Fernão Cardim,

it is possible to detect the first ever performance of the Brazilian

Pastoral on January 5th 1584 - Twelfth Night. This fact is also referred

to by Mario de Andrade in his publication Brazilian Dramatic Dances

-" Beneath an arbor, native Brazilians presented a pastoral dialogue in

the Brazilian language, Portuguese and Castilian [Spanish dialect].

They seem to take great delight in speaking the pilgrim language,

principally the Castilian. There was excellent singing, flute music and

dance, after which we all proceeded, in an inventive procession, to the

church".

THE PASTORAL IN PERNAMBUCO

It

is curious to observe that during the 17th and 18th centuries, there is no

relevant documented evidence

concerning the pastoral . However, once

the 19th century begins, there is an abundance of pastoral presentations,

especially in the Northeast of Brazil, and more specifically in the states

of Pernambuco and Bahia. These texts were actually published, as in the case of

those by Sylvio Romero and Pereira da Costa.

Mário de Andrade observes the strange fact that there were repercussions

of this dramatic dance on a national level - but only during the

eighteen hundreds when the pastoral was at its height - and then it just

seems to have disappeared. The Nativity scenes, however, remained popular and became

traditional throughout the entire country. Possibly, as Mário de Andrade

points out, this was due to the strong influence and imposition of the

elite - the bourgeoisie.

In Recife, as well as other Northeastern cities, the Pastoral

shepherdesses sang religious songs before the Nativity scene, not only

enlivening an otherwise static scene, but also adding a sense of drama to

the scene. It is clear that such presentations permitted a greater

understanding of the birth of Christ. And so, in this manner, with the

introduction of visual effects and sound, the scene began to take on life.

Hermano Borba Filho notes that this dramatization brought with it certain

literary influences from the Spanish sacramental 'autos'.

PROFANE-

RELIGIOUS

By setting off in new directions, the Pastoral Plays (Autos)

become transformed into a profane-religious syncretism, and as in most

cases, with an even stronger emphasis on the profane. This was responsible for

the introduction of new elements, especially the licentiousness of the Old

Shepherd and the sensuality of the

Shepherdesses.

In Recife, circa 1840, societies began appearing with the aim of producing

Nativity plays of the Messiah with solemnity, brilliance and decency. Such

theatrical presentations, by groups such as The Christmas Society and The

New Pastoral Society were recorded by Perreira da Costa. With the

formation of these new societies, the pastorals began to take on a

literary form. Poetry would be

recited, and authors and song writers created lyrics and music. Out of

many who contributed, the two brothers João and Raul Valença deserve special mention. Every year they were responsible for a Nativity play very

similar to those of the eighteen hundreds. Ascenso Ferreira reveals that

in Recife, the grandfather of the Valença brothers played in a Nativity play for the first

time at the height of the Paraguayan war in 1865. The

tradition was maintained until 1900 by the brothers' father, who after a

short interrupted period, brought back the nativity plays in the grounds of

their small estate with the same characteristics as the sacramental 'autos'

. The characters that the brothers used in their plays were : Guilt,

Liberty, Religion, Grace, Gabriel, Shepherdesses, Lusbel -the force of

evil, The

Mistress, Diana, The Assistant Mistress, Eve, Argemiro, The Monk, Flora,

Herod, A Centurion, and Cingo.

SHEPHERDESSES FROM

THE PLAY "MANGABA COM CATUABA". Newspaper archives |

|

It is

clear that, although these societies did all in their power to

maintain moral dignity and religiousness, and avoid burlesque or

lurid scenes, the so-called profane pastorals were to be found on

almost every street corner. They were considerably altered from

their original form, and they counted on audience participation to

enliven the scenes. They escaped from the storyline and theme, and

according to many 'separatists', were irreverent, licentious and

immoral.

|

The effort

of the societies to try and maintain an air of serenity in the sacred acts

that they presented also caught the attention of the local press. The

newspapers of the time heavily censured the indecency of certain nativity

plays that were being performed. They even suggested that the

police should intervene and stop such presentations, in order to keep

moral order and respectful customs. There are records from 1840 of such

complaints, for example, those from the newspaper O Carapuceiro

written by Friar Miguel do Sacramento Lopes Gama, known as Father

Carapuceiro and famous for his criticisms of certain customs at the

beginning of the 19th century.

It is for sure that the Pastoral had its

greatest moments during the first twenty five years of the 20th century.

There were numerous lay presentations that did not lose any of their

religious connotations, principally those of the Christmas Cycle. The Nativity Plays were always performed by

'young girls of good

families', who, dressed as shepherdesses, would collect offerings such

as flowers, cakes, perfume and fruit, which would become the prizes at

auctions to raise funds for religious institutions or charities.

From this moment, the pastorals began to

spread throughout all the districts of the city, always certain of attracting a

participative public. Of course, the more licentious the pastoral

became, then the more it would attract the men. Within the structure of the 'auto',

the shepherdesses with their tambourines or maracas, sang and danced to

the sound of a string and wind orchestra, although the structure of the

group very much depended on the financial position of the group. Some of

the groups were able to afford cornets, trombones, clarinets and drums.

Others were accompanied by violins and ukuleles, with a soloist wind

instrument.

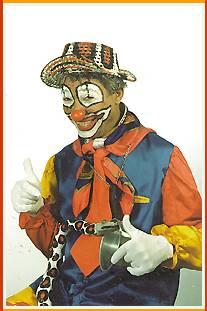

THE OLD MAN - XAVECO.

Jaime Photographs |

|

In

between the two lines, each commanded by their Mistress (in

the blue line) and the Forewoman (the incarnate/red line), we find Diana, who is dressed half red, half blue. The Old Man, known

by the name Bedegueba, but also by numerous other nicknames, is a

kind of buffoon, a circus clown. He commands the 'jornadas'

(the shepherdess' songs) and tells many jokes and runs the

proceedings with much improvisation. His dialogues with the

shepherdesses are riddled with double meanings, and he engages in

discussions and games with the audience. He gets up to many capers and

also sings songs, which have been adapted for his own particular

needs. Amongst the other characters of the Profane Pastoral, there is

to be found the Angel and the Star of the North, the Gypsy and other

characters that can be added depending on the particular region.

Today the pastoral has lost its hieratic and lyrical sense, but has

been transformed into a popular presentational genre. It has taken

on an entirely differentiated form, which it has made entirely its own. It is

not a question of involution, but rather, an interference of the

popular performers, who with their playful and unquiet spirits have

conduced this manifestation. |

|

THE 'AUTO'

The

'auto' tells the story of the shepherds on their way to Bethlehem,

where Jesus was born. The character, Lusbel - representing the

forces of evil, tries every within his

power to deviate the shepherds from their path. He is unsuccessful,

thanks to the interference of Saint Gabriel. Frustrated, Satan

convinces Herod to introduce the slaughter of the baby boys, but

this also fails because the soldiers actually kill his own son. Herod repents

and is saved, while the Devil, once more, is defeated.

The 'auto'

is written in verse and is performed to music. It begins with a

prologue, contains two acts and finishes with an epilogue. The

characteristics are similar to those of a sacramental 'auto', as

mentioned above. The aspect of gathering people together, one of the

strong characteristics of Northeastern popular presentations,

little by little, also began to appear. Perhaps, as Hermilo Borba

Filho points out, as well as attracting a larger public, it was also

to give the authors a greater liberty in creating their works. With

the shepherdesses divided into two groups, blue and red, there was a

possibility of forming 'supporter' groups - who would root for their

favorite color and very often end up brawling. The auction also caused

much excitement, and when the pastoral stopped being less amateur

and took on an air of professionalism, the sensuality and sexuality

were accentuated. Very often the presentation finished with either

the Mistress or the Forewoman or Diana being

kidnapped.

|

THE

'JORNADAS'

In the Nativity scenes that

maintain the traditions of Christmas, we find in the 'jornadas' -

the songs - strong allusions to the birth of Christ :

Da cepa nasceu a rama

From the vine grew the branch

Da

rama nasceu a flor,

From the branch grew the flower

E da flor nasceu Maria

From the flower was born Mary

Mãe de Nosso Senhor.

Mother of our Lord.

or even in the final songs of the

presentation, which make part of the commonly referred to section - 'the

burning of the grotto' - we come across songs with a hieratic aspect,

when the shepherdesses sing :

Vamos companheiras, vamos,

Let's go, companions, let's go,

Vamos a Belém,

Let's go to Bethlehem,

Para queimar as palhinhas

Let's go to burn the straw

Onde nasceu nosso bem. Where our Lord

Jesus was lain.

The burning of the Nativity grotto took

place almost always on Twelfth Night, when the families received guests

for the traditional midnight celebrations. They would carry all the dry

leaves, which had decorated the Nativity scene, to be burnt on a bon-fire at

the door of the church. The participants would form a circle around the

fire and they would sing the appropriate song :

|

|

A nossa lapinha

Our little grotto

Já vai se

queimar Is going to burn

E nós,

pastorinhas, And we, the shepherdesses

Devemos

chorar. Will surely shed a

tear.

Queimemos, queimemos, We Burn, We Burn,

A nossa lapinha,

Our little grotto scene

De cravos, de rosas,

Of cinnamon, and roses

De belas florinhas

Of such pretty posies.

Queimemos, queimemos, We Burn,

We Burn,

Gentis pastorinhas,

Sweet shepherdesses,

As secas palhinhas,

The dry straw

Da

nossa lapinha... Of our little

grotto scene.

|

This

was the time to throw onto the fire, all the written favors and requests

to the Child Jesus. After this, everyone would return home, where a plentiful supper was waiting for

them and the fun would continue. However, in the

so-called Profane Pastoral it is only the opening and closing songs that

make any reference to the birth of Christ. And even then, not always.

Amongst the innumerous versions of the opening songs, they are still sung

in the following fashion :

Boa-noite,

meus senhores todos

Good evening to all the gentlemen

Boa-noite, senhoras também;

Good evening ladies too;

Somos

pastoras

We are shepherdesses

Pastorinhas belas

Pretty little shepherdesses

Que alegremente

Who are happily

Vamos a Belém.

On our way to Bethlehem

Sou a Mestra

I am the Mistress

Do Cordão encarnado

Of the Red Line

O meu cordão

I know how to dominate

Eu sei

dominar

My line

Eu peço palmas

I ask for applause

Peço riso e flores

I ask for smiles and flowers

Ao partidário

And to our supporters

Eu

peço proteção.

I ask protection.

Sou a contramestra

I am the Forewoman

Do cordão azul

Of the Blue line

O meu

partido

I know how to dominate

Eu sei dominar

My group

Com minhas danças

With my dances

Minhas

cantorias

With my songs

Senhores todos

Ladies and Gentlemen

Queiram desculpar

I ask your forgiveness

Diana, while she is the

mediator, sang:

Sou a Diana, não tenho partido

I am Diana, I have no group

O meu partido são os dois

cordões,

My group is the two lines

Eu peço palmas, fitas e flores

I ask for applause, ribbons and flowers

Ó meus senhores, sua

proteção.

And ladies and gentlemen, your protection.

It

is important to add that these choreographed songs appear one after the other, with no dialogue or texts to link

them, except for when the Old Man irreverently interferes in the

proceedings with his improvisations to stimulate the public, or to receive

any tips that might be thrown to him.

Today, in

terms of being a popular show, the pastoral has lost much ground, and it

is difficult to find many groups bringing this traditional pleasure to the

neighborhoods of the city, on improvised stages in the local square. It is

common to hear people saying, "you don't see pastorals at the end of

the streets like you used to any more, bringing their popular, irreverent

happiness". This manifestation has lost its social function, and

sadly we have also lost many of those familiar, popular actors who

performed the part of the Old Man, actors such as :Amaro Canela de Aço, Catota, Galo Velho, Cebola, Baú,

Velho Barroso, Futrica and Faceta.

However,

even though certain economic and social factors have been responsible for the

decadence of the pastoral, it is important to remember the resistance of

the famous 'Old Man Xaveco and his Shepherdesses'. He has issued new CD's

and theatre shows have been presented. Also, the actor Walmir Chagas has

recreated the famous old character of The Old Man Mangaba.

|